What is a Curative Instruction? A Comprehensive Guide

Curative instructions are directives from a judge to a jury‚ aiming to counteract prejudicial effects during a trial‚ often stemming from improperly admitted evidence.

These instructions‚ also known as evidentiary instructions‚ seek to ‘cure’ any harm caused by inadmissible or improperly presented information‚ ensuring a fairer verdict.

Gmail‚ a secure email service‚ exemplifies how information needs clarity; similarly‚ curative instructions clarify trial proceedings for the jury’s understanding and decision-making.

Curative instructions represent a crucial procedural tool within the American legal system‚ designed to address instances where potentially damaging or inadmissible evidence has been presented to a jury. These instructions‚ delivered by the presiding judge‚ aren’t about preventing errors – they’re about mitigating their impact. Essentially‚ they are a judicial attempt to “unring the bell‚” acknowledging that while the jury heard something problematic‚ they should not consider it when reaching a verdict.

The core function is to refocus the jury’s attention on the admissible evidence and the applicable law. They come in various forms‚ each tailored to the specific issue at hand. Like ensuring clarity in a service such as Gmail‚ where confirmations are synchronized‚ curative instructions aim to streamline the jury’s understanding. They are a recognition that perfect trials are rare‚ and the legal system must have mechanisms to address inevitable imperfections‚ striving for a just outcome despite them.

These instructions are a vital component of ensuring a fair trial.

Historical Context of Curative Instructions

The historical development of curative instructions is interwoven with the evolution of evidentiary rules and the pursuit of fair trial procedures in common law systems. While a precise pinpoint of origin is difficult‚ the need to address prejudicial evidence arose early in legal proceedings. Initially‚ judges relied on general admonitions to juries‚ urging them to disregard improper statements or evidence.

Over time‚ these admonitions became more formalized‚ evolving into specific‚ tailored instructions. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw increased emphasis on defining the scope and limitations of such instructions‚ mirroring the growing complexity of trial practice. Much like the development of secure email systems like Gmail‚ prioritizing privacy‚ legal procedures adapted to address emerging challenges.

The modern framework for curative instructions is largely shaped by codified rules of evidence‚ aiming for consistency and clarity in their application‚ ensuring a more equitable legal process.

The Purpose of a Curative Instruction

The core purpose of a curative instruction is to mitigate the potentially prejudicial impact of improperly admitted evidence or statements made during a trial. It’s a judicial tool designed to ‘cure’ any harm caused‚ ensuring the jury’s decision is based solely on admissible evidence. This isn’t about erasing what the jury heard – akin to unringing a bell – but rather directing them to disregard it.

Essentially‚ the instruction serves as a corrective measure‚ reinforcing the jury’s duty to follow the law and avoid being swayed by irrelevant or inadmissible information. Like Gmail’s filters reducing spam‚ curative instructions aim to filter out damaging‚ yet improper‚ influences.

The goal is to preserve the integrity of the trial process and guarantee a fair verdict‚ upholding the principles of due process and ensuring justice is served‚ despite procedural errors.

Distinction Between Standard and Curative Instructions

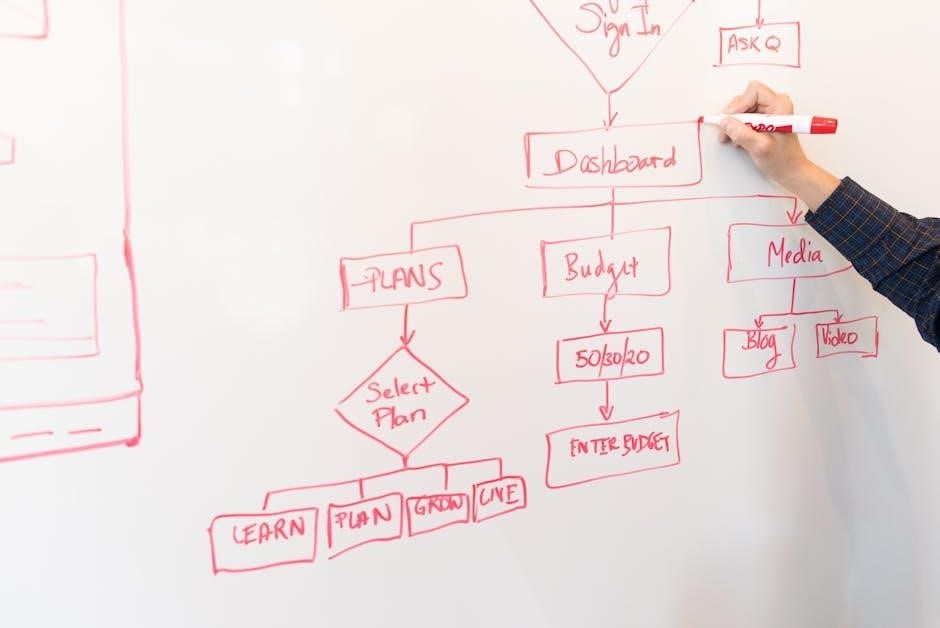

Standard instructions are pre-defined legal guidelines given to the jury before deliberation‚ outlining the applicable law and their duties. Conversely‚ curative instructions are reactive – issued in response to specific events during trial‚ like inadmissible evidence. Think of standard instructions as the foundational rules‚ and curative instructions as addressing mid-game corrections.

While standard instructions proactively guide the jury‚ curative instructions attempt to remedy a potential prejudice that has already occurred. They don’t establish law; they clarify how existing law applies to a specific situation.

Like Gmail automatically categorizing emails‚ standard instructions organize the legal framework. However‚ if a harmful email slips through (inadmissible evidence)‚ a curative instruction is needed to direct attention away from it‚ ensuring a fair assessment.

When are Curative Instructions Given?

Curative instructions are typically given when improper evidence is presented‚ prejudicial statements are made‚ or witness misconduct occurs during a trial’s proceedings.

They address immediate issues to safeguard a fair trial.

Responding to Improperly Admitted Evidence

Curative instructions frequently arise when evidence slips in that shouldn’t have been admitted in the first place. This can happen despite a judge’s best efforts to maintain proper procedure‚ or through unforeseen circumstances during testimony. The core purpose of the instruction in these scenarios is to tell the jury to disregard the problematic evidence entirely.

However‚ simply telling jurors to ignore something isn’t always effective – the “bell that cannot be unrung” analogy is often used. Therefore‚ the instruction must be carefully worded. It should not draw more attention to the evidence by repeating its details‚ but rather‚ firmly direct the jury to treat it as if they never heard it.

The instruction’s success hinges on the judge’s authority and the clarity of the direction. It’s a critical tool for preserving the integrity of the trial and ensuring a verdict based solely on admissible evidence‚ much like Gmail’s security features protect user information.

Addressing Prejudicial Statements by Attorneys

Curative instructions become essential when an attorney makes improper or prejudicial statements during trial. These statements might violate rules of evidence‚ appeal to emotions unfairly‚ or offer opinions disguised as facts. While objections are the first line of defense‚ sometimes a statement gets out before a timely objection can be made‚ or the damage is already done.

In such cases‚ a curative instruction serves to neutralize the effect of the attorney’s misconduct. The judge directs the jury to disregard the statement and refrain from considering it during deliberations. Similar to how Gmail filters spam‚ the instruction aims to remove unwanted influence from the jury’s consideration.

The instruction must be prompt and direct‚ emphasizing that the attorney’s statement doesn’t constitute evidence. It’s a vital mechanism for maintaining a fair trial‚ ensuring the verdict rests on legitimate evidence‚ not improper advocacy.

Dealing with Witness Misconduct

Curative instructions are frequently employed when a witness engages in misconduct on the stand. This misconduct can take various forms‚ including offering unsolicited opinions‚ speculating‚ volunteering information beyond the scope of the question‚ or making improper references to inadmissible evidence. Just as Gmail automatically organizes flight confirmations‚ curative instructions aim to restore order to the proceedings.

When witness misconduct occurs‚ the judge may issue an instruction directing the jury to disregard the improper testimony. The instruction emphasizes that the witness’s statement isn’t evidence and shouldn’t influence their decision. The goal is to ‘cure’ any prejudice created by the witness’s inappropriate behavior.

Effectiveness hinges on the promptness and clarity of the instruction. A swift response minimizes the risk of the jury being unduly swayed by the misconduct‚ preserving the integrity of the trial process.

Types of Curative Instructions

Curative instructions manifest as directives to disregard evidence‚ limiting instructions defining evidence scope‚ or clarifying instructions explaining legal concepts—all aiming for a fair trial.

Instructions to Disregard Evidence

Instructions to disregard evidence represent a core type of curative instruction‚ issued when inadmissible or improperly admitted information has reached the jury’s awareness. The judge directs the jurors to completely ignore the specific evidence during their deliberations‚ essentially attempting to erase it from their consideration.

However‚ the effectiveness of these instructions is often debated‚ facing the “bell that cannot be unrung” challenge – jurors may find it difficult‚ if not impossible‚ to truly disregard information they’ve already heard. Despite this limitation‚ courts frequently employ them as a good-faith effort to mitigate prejudice.

These instructions are particularly crucial when evidence is admitted inadvertently‚ or when a witness makes an improper statement. The goal is to prevent the tainted evidence from unduly influencing the jury’s verdict‚ upholding the principles of a fair trial‚ much like ensuring clarity in communications‚ as exemplified by services like Gmail.

Limiting Instructions

Limiting instructions‚ a vital form of curative instruction‚ don’t ask the jury to disregard evidence entirely‚ but rather to restrict how they use it. Unlike instructions to disregard‚ these define the specific purpose for which evidence is admissible‚ preventing jurors from considering it for other‚ improper reasons.

For example‚ evidence admitted to show a pattern of behavior might be limited to that purpose‚ with the jury instructed not to infer a defendant’s character from it. This nuanced approach acknowledges the evidence’s relevance for a specific issue while safeguarding against undue prejudice.

Effectively‚ limiting instructions act as a boundary‚ guiding the jury’s reasoning process. Similar to how Gmail filters emails‚ these instructions filter the jury’s consideration of evidence‚ ensuring it’s applied correctly within the legal framework and promoting a just outcome.

Clarifying Instructions

Clarifying instructions serve as a corrective measure when ambiguity arises during a trial‚ ensuring the jury comprehends legal concepts or the application of evidence. These aren’t responses to specific errors‚ but proactive steps to prevent misinterpretations that could influence the verdict.

They might explain the burden of proof‚ define key terms‚ or elaborate on the elements of a crime. Essentially‚ clarifying instructions aim to remove any confusion that could lead jurors astray‚ fostering a more informed and accurate decision-making process.

Much like Gmail’s organization features help users understand their inbox‚ clarifying instructions organize complex legal principles for the jury. They ensure a shared understanding of the legal landscape‚ promoting fairness and transparency‚ and ultimately‚ a just resolution‚ similar to a detective’s testimony.

Legal Basis and Authority for Curative Instructions

Curative instructions derive authority from rules of evidence‚ like the Federal Rules‚ and state-specific guidelines‚ ensuring trials remain fair despite evidentiary errors.

Case law‚ such as State v. Olajuwan Herbert‚ demonstrates judicial application of these instructions to remedy trial issues and protect due process.

Federal Rules of Evidence & Curative Instructions

While the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) don’t explicitly mention “curative instructions” by name‚ their underlying principles heavily support the practice. Rule 103‚ concerning rulings on evidence‚ allows courts to take measures to mitigate errors‚ including issuing instructions to the jury.

Specifically‚ FRE 103(a) permits objections to evidence‚ and 103(b) details how to preserve a claim of error for appeal. If improper evidence is admitted‚ a timely objection allows the requesting party to seek a curative instruction. The judge‚ possessing discretion‚ can then direct the jury to disregard the evidence or limit its consideration.

This aligns with the broader goal of the FRE – to ensure fair trials. A curative instruction isn’t a guaranteed remedy‚ but it represents a procedural mechanism to address prejudicial errors. The effectiveness hinges on the judge’s promptness and clarity‚ aiming to neutralize the impact of the flawed evidence on the jury’s deliberations‚ much like Gmail’s security features protect user information.

State-Specific Rules Regarding Curative Instructions

Beyond the Federal Rules of Evidence‚ individual states often have specific rules or established case law governing curative instructions. These can vary significantly‚ impacting when and how they are employed.

Some states may have codified procedures for requesting such instructions‚ outlining the required timing and content. Others rely heavily on common law principles‚ granting judges broad discretion. For example‚ states may differ on whether a curative instruction is sufficient‚ or if the evidence requires striking from the record.

The New Jersey case of State v. Olajuwan Herbert demonstrates state-level application. Understanding these nuances is crucial‚ as a curative instruction deemed adequate in one state might be insufficient in another. Like Gmail adapting to different language preferences‚ state rules tailor legal procedures to local contexts‚ ensuring fairness within their jurisdictions.

Case Law Examples: State v. Olajuwan Herbert

The New Jersey Appellate Division case‚ State v. Olajuwan Herbert (2019)‚ provides a practical illustration of curative instructions in action. During the trial‚ a detective’s testimony inadvertently revealed prior bad acts of the defendant‚ information not admissible under the rules of evidence.

Defense counsel requested a curative instruction to mitigate the potential prejudice. The court granted the request‚ directing the jury to disregard the detective’s improper statements and to base their verdict solely on admissible evidence.

The appellate court upheld the trial court’s decision‚ recognizing the importance of curative instructions in safeguarding a defendant’s right to a fair trial. Similar to Gmail filtering spam‚ the instruction aimed to remove damaging‚ irrelevant information from the jury’s consideration‚ ensuring a verdict based on proper evidence.

Effectiveness and Limitations of Curative Instructions

Despite their intent‚ curative instructions face the “bell that cannot be unrung” problem; jurors may struggle to fully disregard prejudicial information‚ impacting verdict objectivity.

Effectiveness hinges on factors like timing‚ clarity‚ and the nature of the prejudice‚ mirroring Gmail’s spam filter accuracy.

The “Bell That Cannot Be Unrung” Problem

The phrase “bell that cannot be unrung” vividly illustrates a significant limitation of curative instructions. Despite a judge’s directive to disregard certain evidence or statements‚ the initial exposure often leaves a lasting impression on jurors. This is because human cognition doesn’t easily suppress information once it’s been processed‚ much like recalling an unwanted memory.

Even with sincere attempts to follow the instruction‚ jurors may subconsciously factor the inadmissible material into their deliberations. The prejudicial impact‚ therefore‚ persists despite the court’s effort to ‘cure’ it. This challenge is amplified when the evidence is particularly inflammatory or emotionally charged‚ making complete disregard exceedingly difficult.

Similar to how a Gmail notification‚ once read‚ cannot be unseen‚ the initial exposure to damaging information during a trial creates a cognitive footprint. While instructions aim to mitigate harm‚ they cannot entirely erase the initial impact‚ raising concerns about the fairness of the trial process and the potential for biased verdicts.

Factors Influencing Effectiveness

The effectiveness of curative instructions isn’t uniform; several factors significantly impact their success. The timeliness of the instruction is crucial – a prompt response minimizes the prejudicial effect‚ while delays diminish its impact. The clarity and forcefulness of the judge’s language also matter; ambiguous or weak instructions are easily disregarded.

The nature of the evidence itself plays a role; highly prejudicial material is harder to overcome than minor infractions. Juror characteristics‚ such as pre-existing biases or levels of cognitive processing‚ can also influence their susceptibility to the instruction.

Furthermore‚ a judge’s overall demeanor and the context in which the instruction is given contribute to its weight. Just as Gmail prioritizes important emails‚ a judge must emphasize the instruction’s importance to ensure jurors prioritize it during deliberations‚ maximizing its potential to mitigate bias.

Criticisms of Curative Instructions

Despite their intent‚ curative instructions face substantial criticism. The primary concern is the “bell that cannot be unrung” problem – jurors may struggle to fully disregard damaging information‚ even after being instructed to do so. Critics argue instructions often highlight the inadmissible evidence‚ drawing more attention to it than if it hadn’t been mentioned at all.

Some legal scholars contend instructions place undue faith in jurors’ ability to compartmentalize information‚ a cognitive task proven difficult. The reliance on instructions can also discourage attorneys from diligently objecting to improper evidence initially‚ assuming a ‘cure’ is available.

Similar to how Gmail filters spam but isn’t foolproof‚ curative instructions aren’t guaranteed to eliminate prejudice. They are often seen as a less effective remedy than preventing the evidence’s admission in the first place‚ raising questions about their overall utility.

Requesting a Curative Instruction

Requests should be timely‚ made after prejudicial statements or evidence‚ and contain precise wording to address the issue‚ anticipating potential objections from opposing counsel.

Timing of the Request

The timing of a curative instruction request is critical; it must be made promptly after the prejudicial matter occurs. Delay can diminish its effectiveness‚ as the jury’s initial impression may solidify. Ideally‚ a request should be made before the jury begins deliberating‚ allowing the judge to address the issue while the evidence is still fresh in their minds.

However‚ a request made during closing arguments can still be considered‚ particularly if the prejudice is ongoing or cumulative; Failing to object contemporaneously to the improper evidence might waive the right to a curative instruction‚ depending on jurisdiction. Like Gmail’s instant synchronization‚ a swift response is vital.

The goal is to mitigate harm immediately‚ preventing the jury from being unduly influenced by information they shouldn’t have considered. A timely request demonstrates diligence and protects the integrity of the trial process‚ ensuring a fair outcome.

Proper Wording and Content

Curative instruction wording must be precise and neutral‚ avoiding any language that could further emphasize the inadmissible evidence. The instruction should clearly state what the jury should not consider‚ without repeating the damaging information itself. It’s crucial to avoid drawing undue attention to the issue while still adequately addressing the prejudice.

The content should focus on the legal principle violated‚ guiding the jury to disregard the specific evidence. Like Gmail’s clear interface‚ instructions should be easily understood. Avoid argumentative language or attempts to re-litigate the evidence.

A well-crafted instruction will simply and directly tell the jury to disregard the improper matter and continue deliberations based solely on admissible evidence‚ ensuring a fair and impartial verdict.

Potential Objections to the Instruction

Opposing counsel may object to a curative instruction on several grounds. A common objection is that the instruction unduly emphasizes the inadmissible evidence‚ potentially exacerbating the prejudice it aimed to cure – the “bell that cannot be unrung” problem.

Another objection centers on the instruction’s accuracy or neutrality‚ arguing it misstates the law or subtly directs the jury towards a specific conclusion. Like ensuring Gmail account security‚ legal precision is vital.

Objections may also arise if the instruction is deemed repetitive or cumulative‚ or if the requesting party failed to timely object to the initial improper evidence. Successfully navigating these objections requires careful drafting and a clear understanding of evidentiary rules.